Artist in Residence Program

2020 Resident Artist

ARCUS Project’s Artist-in-Residence Program received 487 applications from abroad (77 countries and regions), 23 applications from the Netherlands (12 countries and regions) and 17 applications from Japan. Following a careful screening process, Ieva Raudsepa (Latvia), millonaliu [Kilodiana Millona & Yuan Chun Liu (Albania/Taiwan)] and OLTA (Japan) have been selected as the 2020 residents. The artists will participate in an online residency for 85 days from December 3, 2020 to February 25, 2021.

As the judges for this year’s applications, we welcomed Iseki Yu, a curator at Contemporary Art Center, Art Tower Mito and Tokuyama Hirokazu, an associate curator at Mori Art Museum who made the selection through a process of discussion with the ARCUS Project Administration Committee.

Overview of the 2020 Selection

For the 2020 residency program, we had three applicant categories (artists from abroad, artists from Japan, and artists based in the Netherlands), from each of which one artist or artist group was selected.

Immediately prior to the start of the application period, the World Health Organization declared the novel coronavirus crisis a global pandemic, and we accordingly expected a significant decline in the number of applications this year. The fact that we still received many applications, especially from Europe and Asia as with last year, and that the total number was 527 applicants―a relatively modest decline of 20 percent from last year―gave us a sense of the extent to which artists remain committed and passionate about creating work.

Looking at the applications as a whole, there was a slight increase in the number of proposals to research and produce something in a way that brought together the interests of the artist and the specific nature of ARCUS Project’s location in Moriya City, Ibaraki Prefecture. It was difficult to choose which was better among, for instance, the plans inspired by pearl cultivation in Lake Kasumigaura, the others based on agricultural history and research, or the proposals that examined changes in lifestyle and communication during urbanization and suburbanization. Following discussions, we selected artists whose work indicated both high quality in regard to concept and production, and versatility in terms of development.

(Director, Ozawa Keisuke)

Ieva Raudsepa

Latvia

Photo: Alia Ali

Born in Riga, Latvia, in 1992, Ieva Raudsepa is now based in Los Angeles. After studying philosophy at the University of Latvia, she received an MFA at the California Institute of the Arts. As someone born following the independence of Latvia from the Soviet Union, and brought up during the subsequent period of transition from communism to capitalism, Raudsepa’s work attempts mainly through photography and video to capture her fellow members of this young generation that emerged immediately after the collapse of the Soviet Union. In her video practice, she creates narratives by effectively fusing theory and fiction, and then re-questions these narratives at a metalevel. Alongside revealing the fictionality of a performance by having actors perform in everyday spaces, she is interested in what actual circumstances tell us by chance.

Selected Works

Interviewing the architectural historian Taro Igarashi

Curator visit (Shihoko Iida)

Artist Statement

The starting point of my research was the five-minute long scene of a drive on urban highways from the 1972 Andrei Tarkovsky film Solaris. The episode was shot in the Tokyo districts of Akasaka and Iikura in 1971. The scene mixes black and white footage with color and some portrait shots, and is an interplay of time, space, and perception. In the movie, the parts shot in Tokyo represent a city of the future.

My research process was based on a set of questions. I was interested in the politics entwined in this episode. How did a Soviet film director decide to film “the future city” in Japan? As travel outside of the USSR was very restricted for Soviet nationals, did Tarkovsky experience any difficulties in the production of the scene? Why did he choose to shoot on the expressways and what is the history of the design and construction of the Shutoko—the Metropolitan Expressway—in Tokyo? How did construction of high-speed intercity roads change the fabric of the city? What are other examples depicting Tokyo as a future city in popular culture and imagination?

The ARCUS residency gave me the opportunity to explore these questions both by examining existing literature, images, and film, as well as interviewing experts in Japan and elsewhere. Additionally, I was able to meet with local curators to speak about previous projects and the research in progress. The ARCUS team gave me great support with getting in touch with people and institutions, as well as helping generate new ideas as to where to look, what to read, and with whom to speak.

I am now putting together all the knowledge and different histories I have gathered into something that will turn into a script or a structure for a video piece. Out of the research I have conducted, there are two main threads I am exploring in the video piece. The first is the representation of Tokyo as the city of the future. I am interested in the perception of the city in the context of postwar infrastructural development in Japan—the Shutoko being an example of this. Besides what was actually built, Tokyo as a future city has been represented in the imaginations of architects, writers, and filmmakers. I am interested here in the Metabolist movement as well as techno-orientalism.

The second main thread I am using is the speculative history of the production of the highway scene in Solaris and the Tarkovskian way of seeing the world as a set of metaphysical questions about life, death, love, and the meaning of human existence, and how that relates to visions of the future. I am exploring this while keeping in mind that Andrei Tarkovsky was a film director living and producing movies under a political regime that limited and censored his work. I will create fictional narratives for the video, while referring to the research I have conducted during the residency in 2020, and I will film it when it is possible to physically go to Japan.

Reason for Selection

Ieva Raudsepa plans to make a video work inspired by Solaris, the 1972 film by Andrei Tarkovsky. Solaris features the then newly constructed Shuto Expressway, a highway in Tokyo, as a symbol of the future city. The Shuto Expressway, which facilitates high-speed movement, encompasses both a sense of a present day where the prior rhythms of the city are dismantled while new rhythms are formed as well as premonitions of a future where this will accelerate even further. Raudsepa plans to conduct online research on the changes to Tokyo caused by the construction of the Shuto Expressway, and then write a script interweaving this with fiction. In our present, where economies and people’s lives have slowed down due to the coronavirus pandemic, Raudsepa’s practice will explore with a skeptical eye how modern society desires and mythologizes speed. (Director, Ozawa Keisuke)

millonaliu [Klodiana Millona & Yuan Chun Liu]

Albania/Taiwan

Photo: Pichaya Puapoomcharoen

The Rotterdam-based millonaliu is a duo of spatial designers and researchers comprising Klodiana Millona from Albania and Yuan Chun Liu from Taiwan. After studying interior architecture at the Royal Academy of Art, The Hague, they began developing interdisciplinary activities with a focus on architecture. The duo’s work encompasses everything from architectural practice to video, publishing, exhibitions, and workshops. Made during a stay in Ukraine, Leave Us Alone examines factories left behind after social change, and by holding a festival in collaboration with workers, millonaliu highlighted the social aspect of factories whereby an isolated community is formed while the times move on.

Selected Works

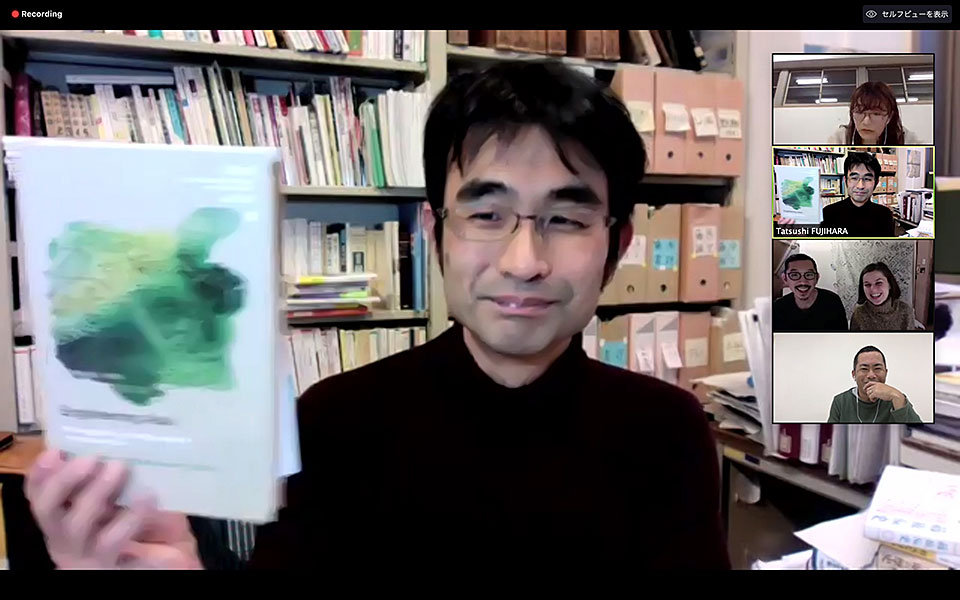

Interviewing the agricultural historian Tatsushi Fujihara

Interviewing the agronomist Yoichiro Sato

Artist Statement

Sticky Entanglements: Rice as a Technology

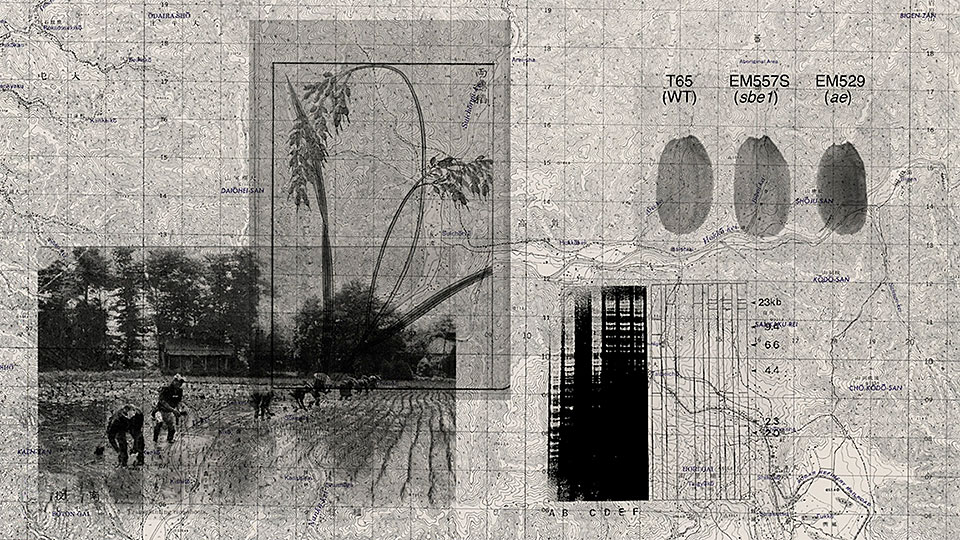

During the three-month residency, we have been exploring Hōrai rice, which is the manifestation of the Japanese Empire’s seed engineering project in colonial Taiwan, whereby a type of rice was brought to the island and genetically modified to grow in Taiwan’s tropical climate when it was a colony of Japan from 1895 to 1945.

Sticky Entanglements refers, on the one hand, to the particular feature of Japonica rice, a much-desired stickiness that led to a series of scientific, political, and economic efforts to modify Taiwanese local rice so as to satisfy Japanese taste. On the other hand, it describes almost literally our research approach during these three months, where starting from one grain of rice we mapped different entanglements that are glued together as a way to understand the legacy of genetically modified crops within colonialism, politics, science, technology, the environment, and economics.

As our main method, we have studied different archives as well as related literature, and conducted interviews with scholars in the field. We developed a particular interest in archives of postcards from East Asia during the Japanese occupation.

Our research primarily focused on the vast changes reflected in the landscape that the cultivation and commercialization of this crop brought to Taiwan, and how control over the land was instrumentalized as a technology for control over the population. This culminated in us exploring social changes that resonated in local culture and labor practices.

Hōrai seeds have left a strong legacy both physically and socially in Taiwan of intentionally planned ecological transformation through state-engineered and scientifically improved seeds. This form of advanced ecological imperialism took control of economic, ecological, and natural resources away from local inhabitants, resulting in the modification of their ecology and culture. Our research tries to read the current condition of soil as a form of evidence and crops as witnesses that shed light on these issues.

Finally, through this research we want to address, understand, and make visible the multiple entanglements deriving from a tiny grain of rice. By addressing this seed as a technology for social engineering, we tried to unfold the narratives of the ideology engineered in this nonhuman material. For the next phase, we aim to disseminate this knowledge through field research and to advance the practice of looking at seeds as a biosocial archive.

Reason for Selection

Through research on Hōrai rice, a type of rice brought to Taiwan when it was a colony of Japan, Klodiana Millona and Yuan Chun Liu will focus on the rice crop improvements that took place at that time within the entanglement of politics, technological innovation, land improvement, and economics. Deconstructing the image the West tends to have about Taiwan as an abundant and peaceful land, this project continually probes the intrinsic historical correlation between agriculture in Taiwan and powerful nations. The duo plans to conduct work online through doing research at an archive about Meiji-era (1868–1912) foreign policy and speaking with experts. The project is expected to reveal perspectives objectively interpreting present-day agriculture alongside subtly illuminating aspects of farmland and crop development in terms of how governance has historically related to rice and the land. (Director, Ozawa Keisuke)

OLTA

Japan

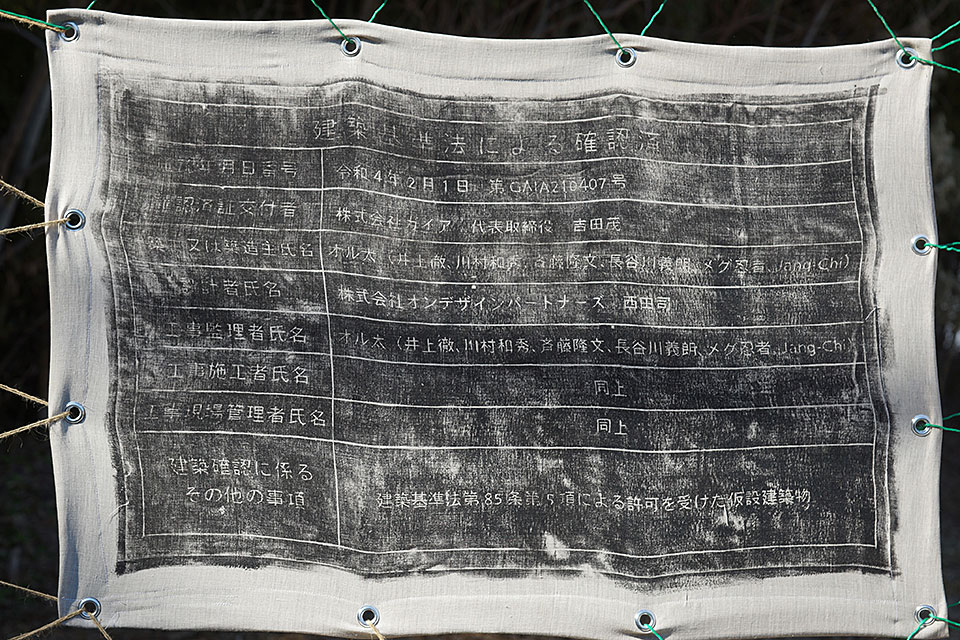

Photo: Shingo Kanagawa

OLTA is a group of six artists formed in Tokyo in 2009. Its practice to date has focused on collective acts within particular communities like games and festivals, and the communication that unfolds there, which it has reconfigured and re- enacted in such works as Hyper Popular Art Stand Play and TRANSMISSION PANG PANG. Its recent work Cultivate House saw the group undertake cultivation and production at a mobile home built on untilled land. OLTA’s practice disrupts the foundations of various communities, and brings out the ideas, customs, language, and lifestyles that underpin these.

Selected Works

Participating in a composting workshop with the soil ecologist Nobuhiro Kaneko in Fukushima

Artist Statement

In order to carry out Cultivate House as an artwork where we build our own home and question what it means for a person to live in terms of the relationship with the soil and farming, we conducted research on no-till farming and soil environments appropriate for growing crops. In Lived-in Houses, Koji Taki describes how the house is a form of time and has life through humans but simultaneously decays. Possessing the bare minimum elements required for a house by having a toilet and triple bunk bed in a temporary hut structure, Cultivate House is a living house that coexists with things that decay, such as the mold and rust that grow on the materials, flies, and the bacteria that breaks down waste in the composting toilet. At Cultivate House, exposing as it does the functions of pipelines that are always buried in the ground or inside walls in housing today, we reflect on the kinds of artistic practices that can be done from the natural processes carried out there.

To learn first which natural environments are appropriate for cultivating, living, and working at Cultivate House, we visited candidate sites for the project with Tsuyoshi Miyazaki, an expert on soil hydrology, and heard about their soil and suitability for farming. In the center of Moriya is the Sashima plateau, while its lowlands that lead to the rivers Tone, Kokai, and Kinu form a small valley called Yato. The soil comprises Joso clay and the volcanic ash soils that have accumulated on top. At the abandoned rice fields that we observed in Yato, sunlight is blocked by bamboo groves, while the fertile volcanic ash soils in the top layer are washed away by the water that flows down from the mountain. This kind of soil environment is unsuitable for growing crops, and, since it poses similar problems also in terms of living there, such as the lack of sunlight and drainage, we determined that it would be difficult to live on this land, and decided to search for a place with more light.

We then visited a farm in Moriya called jivana for an introductory experience of farming. At jivana, along with growing crops on cultivated land, they harvest true-breeding plants, raise their own seeds, and carry out no-till farming. This latter is a form of farming where you grow crops without disturbing the soil, and thus preserve the ecosystem of the soil. The wood on the site also has a kind of bamboo jungle gym and a handmade oven where it is possible to bake pizza, making the farm a leisure spot for playing and working together. Here we learned about approaches to farming that are synched with the long-term cycles of the land and cultivation, as well as about the approaches of a community through the play that happens alongside that farming.

To further our understanding of no-till farming, we met with the soil ecologist Nobuhiro Kaneko and visited Nihonmatsu in Fukushima Prefecture. We learned that soil nutrients are enriched by compost in order to enhance the quality of the soil. The compost is fermented from the materials obtained on a farm, such as rice husks, sawdust, rice bran, fallen leaves, and soil. A loose community is formed here where that way of making compost is shared among local people.

We had previously thought that soil and art become richer through cultivation, but having studied decay, flood control, and soil ecosystems, and learned that not tilling the soil actually makes it richer, we now, through our practice and while standing on the ground, want to turn to the question of what emerges when engaging with farming, influenced as it is by environmental change and the circumstances of the land, from the perspective of art.

Reason for Selection

For its ARCUS Project residency, OLTA will create a version of Cultivate House. The group will build a mobile home and toilet on a plot of land in Moriya City, where the members will alternately reside and till the uncultivated land, while the toilet will be used as a composter to turn human waste and food waste into fertilizer. Arriving at new realizations and gaining insights day by day as they live there, the members will then harness these in their subsequent lives. The group will conduct online research with a focus on movements and historical evidence regarding the relationship between agriculture and modernization in Japan, and attempt to verify its own activities from a critical position. Both artists and the land being open to processes of becoming, immersed in nature rather than standing in opposition to it, offers beneficial perspectives and ways of living in these troubled times when we face the challenges of climate change and the coronavirus pandemic. (Director, Ozawa Keisuke)